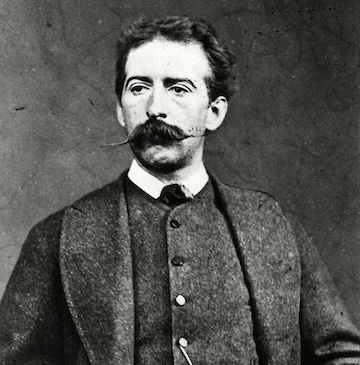

Winslow Homer Biography

Winslow Homer was an American landscape painter and printmaker, best known for his marine subjects. He is considered one of the foremost painters in 19th century America and a preeminent

figure in American art.

Largely self-taught, Homer began his career working as a commercial illustrator. He subsequently took up oil painting and produced major studio works characterized by the weight and density he exploited

from the medium. He also worked extensively in watercolor, creating a fluid and prolific oeuvre, primarily chronicling his working vacations.

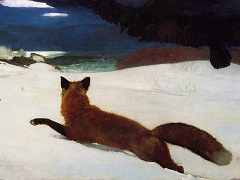

Some major artists create popular stereotypes that last for decades; others never reach into popular culture at all. Winslow Homer was a painter of the first kind. Even today, 150 years after his birth,

one sees his echoes on half the magazine racks of America. Just as John James Audubon becomes, by dilution, the common duck stamp, so one detects the vestiges of Homer's watercolors in every outdoor-magazine

cover that has a dead whitetail draped over a log or a largemouth bass, like an enraged Edward G. Robinson with fins, jumping from dark swamp water. Homer was not, of course, the first "sporting artist" in

America, but he was the undisputed master of the genre, and he brought to it both intense observation and a sense of identification with the landscape-just at the cultural moment when the religious Wilderness

of the nineteenth century, the church of nature, was shifting into the secular Outdoors, the theater of manly enjoyment. If you want to see Thoreau's America turning into Teddy Roosevelt's, Homer the watercolorist

is the man to consult.

The Homer sesquicentennial (he was born in 1836 and died in 1910) is being celebrated with "Winslow Homer Watercolors," organized by Helen Cooper at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. Her catalogue is a landmark in Homer studies. It puts Homer in his true relationship to illustration, to other American art and to the European and English examples he followed, from Ruskin to Millet; its vivacity of argument matches that of the oil paintings. Cooper has brought together some two hundred watercolors-almost a third of Homer's known output. It is a wholly delectable show, and it makes clear why watercolor, in its special freshness and immediacy, gave Homer access to moments of vision he did not have in the weightier, slower diction of oils.

"You will see, in the future I will live by my watercolors," Homer once remarked, and he was almost right. He came to the medium late: he was thirty-seven and a mature artist. A distinct air of the Salon, of the desire for a "major" utterance that leads to an overworked surface, clings to some of the early watercolors-in particular, the oil paintings of fisher folk he did during a twenty-month stay in the northern English coastal village of Cullercoats in 1881-82. Those robust girls, simple, natural, windbeaten and enduring, planted in big boots with arms akimbo against the planes of sea, rock and sky, are also images of a kind of moralizing earnestness that was common in French Salon art a century ago. Idealizations of the peasant, reflecting an anxiety that folk culture was being annihilated by the gravitational field of the city, were the stock of dozens of painters like Paul Cezanne, Van Gogh, Manet and Claude Monet. Homer's own America had its anxieties too - immense ones. Nothing in its cultural history is more striking than the virtual absence of any mention of the central American trauma of the nineteenth century, the Civil War, from painting. Its fratricidal miseries were left to writers (Walt Whitman, Stephen Crane) to explore, and to photographers. But painting served as a way of oblivion - of reconstructing an idealized innocence. Thus, as Cooper points out, Homer's 1870s watercolors of farm children and bucolic courtships try to memorialize the halcyon days of the 185os; the children gazing raptly at the blue horizon in Three Boys on the Shore, their backs forming a shallow arch, are in a sense this lost America. None of this prevented Homer's contemporaries from seeing such works as unvarnished and in some ways disagreeable truth. "Barbarously simple," thought Henry James. "He has chosen the least pictorial features of the least pictorial range of scenery and civilization as if they were every inch as good as Capri or Tangier; and, to reward his audacity, he has incontestably succeeded."

In the 1880's he moved to Prout's Neck, Maine and began painting scenes of the sea and coast. It is interesting to note the contrast in the subject matter of his work. His early work captured the horror of the Civil War, and towards the end of his life, his work captured the peace and serenity of the Maine Coast. Winslow Homer died on September 29, 1910.